THE BRITISH OVERSEAS RAILWAYS HISTORICAL TRUST

|  |

Kevin Jones' Steam Index

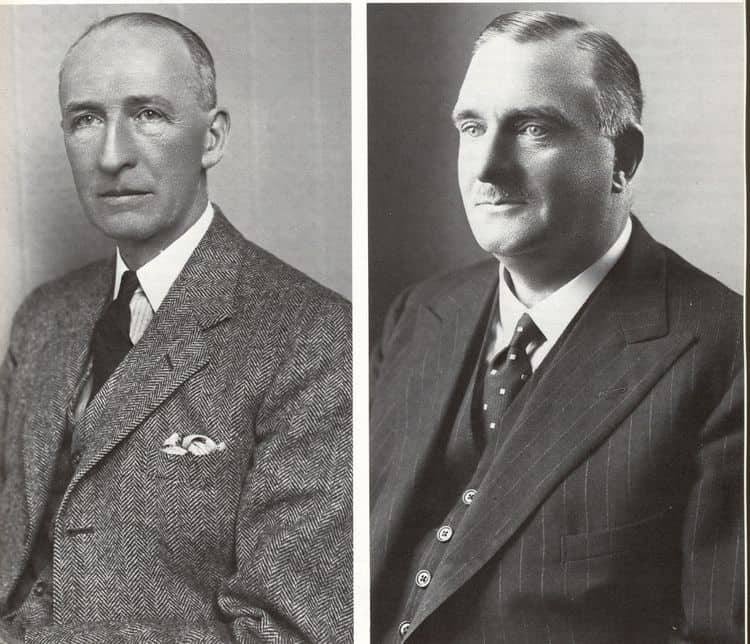

| Edward Thompson & Arthur Peppercorn |  |

Edward Thompson

There is a considerable amount of biographical material relating to Thompson, notably works by Grafton, Hughes and Rogers, the last of whom placed great reliance upon correspondence between himself and several senior officers who survived the period (Roger's describes Thompson's treatment of Spencer as "vindictive"). It is interesting that Thompson appeared to admire Collett and seems to have adopted all of his worst features.

Biography

Edward Thompson was born on 25 June 1881 at Marlborough, the only

son of F.E. Thompson, where his father taught at the famous public

school: Marshall. Edward's grandfather

was the famous architect Francis Thompson see letter by Daunt. He was taught at Marlborough College and at Pembroke

College, Cambridge, where he studied mechanical sciences. An Oxbridge

qualification was rare in a railway mechanical engineer. He began his

practical training at Beyer Peacock and later moved to the Midland Railway,

before joining the Royal Arsenal for one year in 1905. In 1906 he joined

the North Eastern Railway's running dept, leading to his appointment as assistant

divisional locomotive superintendent, Gateshead. In 1913 he married Edith

Gwendolen, younger daughter of Vincent Raven, the

CME. They had no children and she died in 1938. He visited the USA (which

the North Eastern considered to be the source of advanced methods.

Early in 1912 he was appointed Carriage & Wagon Superintendent

on the GNR at Doncaster (Gresley's former position before becoming Locomotive

Engineer (in overall charge of locomotives and rolling stock). ln March 1916

he returned to the Royal Arsenal at Woolwich on war service and in

December 1916 he was sent to France where he was attached to the

headquarters staff of the Director General of Transport. Became lieut col

and was twice mentioned in despatches and was awarded the OBE.

In March 1919 he returned to the GNR, but in 1920 was appointed Manager of

the NER Carriage Works in York

(Locomotive Mag., 1920,

26, 231) (and was succeeded by Bulleid). In 1923 was appointed

Carriage & Wagon manager, NE Area, LNER. In June 1927 he became assistant

mechanical engineer at Stratford, London, and in March 1930 succeeded

G.W.L. Glaze as mechanical engineerr,

Stratford. He was responsible for the highly successful rebuilding of the

1500 class 4-6-0s and Claud Hamilton 4-4-0)s with modem front ends.

On the death of Gresley in 1941 Thompson succeeded

to the position of CME of the LNER, taking over at a period of great difficulty.

Richard Hardy (Steam Wld,

1992 (59) 6) also attended Marlborough, and on the advice of Colonel

Pullein Thompson who visited public schools to provide advice on careers

wrote to the LNER ("Go on the LNER, boy, gentlemen at the top") and was

interviewed by Thompson, who at that time (1940) was Works Manager at Doncaster

who on asking him to attend for interview appended at the end of the letter

"I was at Marlborough many years ago". The eventual interview was extremely

friendly. In this same article Hardy called him "a kind and courteous man"

Hardy also discussed Thompson's relationship with

L.P. Parker.

Beavor had an interview with Edward Thompson in 1942, being received by him in his office. Both he and Gresley were men of great presence and refinement. They commanded a position where the occupant could be as autocratic as he pleased, and indeed was so to a marked extent. While the well-known clash of their personalities was hardly surprising, I found that both were most sympathetic to a young man on the threshold of a career.

K.S. Farr's 'Mallard' memories. (Rly Mag., 1988, 134, 462-3) notes that Edward Thompson was on the footplate on 27 August 1936 when 2512 Silver Fox hauling the Silver Jubilee attempted a fast run down from Stoke Summit and damaged its middle big end.

While he was never a designer of the calibre of his renowned predecessor, Thompson had some commendable motives in design...The most far-reaching of these was to introduce some measure of standardization into the excessive diversity of engine types running about on the LNER.

In Rogers' Express locomotives the Author quotes K.R.M. Cameron who called Thompson's Pacifics "monstrosities" which because of their long wheelbase "developed quite an alarming yawing motion which at times could be quite disconcerting especially to those of us who did ride on them very frequently. Even before [Thompson's] retirement [the Drawing Office] had been thinking about the new engines and tried to prevent them being built with cylinders so far back. In a letter to Rogers, R.C. Symes noted that the "general layout of the first Peppercorn Pacific was in fact on the drawing board (except for the front end) before Peppercorn took over.

Rogers' Thompson & Peppercorn is limited to Thompson and Peppercorn and some extracts are taken from this especially where these have been based on letters received by him from those closely associated with Thompson: During Gresley's time the CME's office had been at Kings Cross. Thompson, who had been Mechanical Engineer Doncaster, decided to stay there (doubtless with the Board's approval) and he arranged his office accommodation accordingly.

Grafton noted that "Shortly after his appointment, Thompson called a meeting of works managers and other senior staff directly responsible to him. As immaculately dressed as ever, he presided in his usual aloof and urbane manner, doing most of the talking. His closing remarks on that occasion were very significant: "I have a lot to do, gentlemen, and little time in which to do it.""

B.C. Symes, via Rogers noted that when Thompson was preparing his scheme for a complete stud of standard locomotives, he browsed through the engine diagrams book which showed all the engines, including those of pre-Grouping design, and picked out those which by dimensions and tractive effort appeared suitable for conversion. Symes added that it was difficult to see any reason for some of his rebuilds of Gresley engines "except to do away with everything Gresley". Symes continued that as far as his standard designs were concerned, Thompson could hardly go wrong with the O1. 'It was the original GC 2-8-0 adopted in 1914 as the ROD engine, and 90 of them went overseas in the 1939-45 affair. By fitting them with modern cylinders (B1) and valve gear, and a B1 boiler, they had a still further lease of life.' In fact the O1 was virtually a new engine, for Harrison says that only the main frames and some of the wheel centres were retained. 'It was a first-class engine', he adds.

Of other rebuilds, Symes noted 'The D49 rebuilt with two inside cylinders was a mystery — only one was done. The B17 rebuilt to B2 was in effect a B1 with larger coupled wheels and to his mind quite unnecessary. So far as the classes that Thompson selected for his rebuilding programme, he thought there were too many. He did not think the A2 was required, in view of the V2 class; the J11 (rebuild of the GC 0-6-0) was not needed, in view of the K1 (two-cylinder rebuild of the K4); and we did not need three types of shunting tank, or the L1 passenger tank, as its work was quite adequately covered by the V1 and V3 types.' Symes draws attention to Thompson's strange choice of GC designs: a pre-1914 heavy goods engine, a light 0-6-0 of 1901, and a 0-8-0 of 1903 'converted to a heavy shunter which nobody wanted'. He added that one would have expected him as a North Eastern man to have chosen from former NE types.

When Symes was in the drawing office at Doncaster, Thompson was frequently in it, discussing various points of design, 'and', he says, 'woe betide the unfortunate who did not hear what he said or ventured to offer an opinion'. Symes adds that 'Thompson had some little photo albums made by our photographers with a picture of one of his proposed standard engines on each alternate page and the engine diagram (line drawing with principal dimensions) on the facing page. One of these was given to each of the Directors and he saw a letter from one of them thanking him for "the beautiful little booklet" and expressing his pleasure at seeing the expert designs.

This booklet must have formed the basis for O.S. Nock's Locomotives of the LNER: standardisation and renumbering pulished by the LNER in 1947 and sold for half a crown. Nock (page 114 et seq: British locomotives of the 20th century. Vol. 2) stated that when invited to Thompson's home in Doncaster during the winter of 1945/6, Thompson informed him of how much he admired the engine lasyout of the GWR 4-cylinder locomotives claiming that the equal length connecting rods of the inside and outside cylinders made it so much easier to get uniformity of valve events and emphasized that this could not be done with the Gresley three-cylinder layout. Nock failed to observe that such an arrangement was also favoured by Raven on the NER. Nock (pages 201-2 British locomotives of the 20th century. Vol. 1) records a conversation which is said to have taken place between Thompson and Stanier in which Thompson is claimed to have stated that he intended to rebuild the Gresley Pacifics with Stephenson link motion for the inside cylinders which horrified Stanier who responded that the LMS had to scrap the Caledonian Railway 4-6-0s which had been constructed with this strange arangement.

Symes also noted that this Director also expressed surprise that association with such masterpieces had not improved the character of his assistant i.e. Peppercorni! E.T. should have burned this, but there it was for anybody looking through the file to see.

Grafton noted that Thompson's office staff suffered some discomfort from his autocratic methods. He had corridor panels reduced in height and panes of glass substituted for the upper portions so that he could walk along the corridor and see what was happening in the general offices. He supervised personally the siting of the office furniture and had the window sills rounded so that it was impossible to put anything on them. He was always the first to arrive in the morning and the last to leave in the evening, and he would periodically carry out an inspection of the offices after everyone else had gone home. R.C. Bond remembered him at conferences when he liked to set out in front of him gold pencils, watches and other symbols of well being. He adds that it was said of him that once he started calling a person by his Christian name it was the prelude to the sack!'

After Thompson's appointment, Peppercorn was moved from Darlington to take up the new post of Assistant Mechanical Engineer and he was also made Mechanical Engineer, Doncaster. The other Mechanical Engineers were: Darlington R.A. Smeddle; Gorton, J. F. Harrison; Stratford, F. W. Carr; and Cowlairs, T. E. Heywood assisted by K. S. Ribertson. B. Spencer, Gresley's Assistant (Technical), was posted elsewhere and replaced by D.R. Edge, and D.D. Gray replaced T.E. Street as Head Locomotive Draughtsman. Future locomotive design was apparently to be inoculated against any danger of posthumous Gresley influence!

Hughes' excellent biography of Gresley casts considerable doubt on the ability of Thompson to act as CME, as perceived by the Company's Chairman:

Although at the beginning of 1941 Sir Nigel was unwell, he was expected to continue in office - indeed this appears to have been his intention - and it does not seem that the LNER Chairman, Sir Ronald Matthews, regarded it necessary to consider the difficult problem of choosing a successor for the post. (It is believed that Matthews assumed that Gresley would go on until he was 70, when he would be succeeded by Arthur Peppercorn, and then Freddie Harrison.) So, when the question arose, it was a matter of urgency. At the time, none of Gresley's senior staff was recognised as his deputy and hence no one was being groomed as a potential successor. Indeed, the only one who might have been regarded as such had been his erstwhile personal technical assistant, Oliver Bulleid, who had left the LNER in 1937 to join the Southern Railway. He had been followed by DR. Edge, a competent manager, but who lacked the breadth of experience needed to fill the CME's position. So, the natural successor in 1941 would have been one of the Mechanical Engineers in the Areas, that at Doncaster being regarded as the senior. This position had been occupied by Edward Thompson since 1938, following similar posts at Stratford and Darlington.

Sir Ronald Matthews lived in Doncaster, and was also Chairman of the Sheffield firm of Turton Brothers and Matthews, and had been Master Cutler. Both Gresley and Thompson were his house guests, and evidently close, as Prudence, one of the Matthews daughters, recalls them as 'Uncle Tim' and 'Uncle Ned'. On paper. Thompson should have been the automatic choice to succeed Gresley. but according to Stewart Cox, Sir Ronald made approaches to his opposite number on the Southern, to see if Bulleid could be enticed back, and the LMS, to enquire after the availability of Roland Bond, whom he had interviewed in connection with Bond's appointment to superintend the joint LNER/LMS locomotive testing station. However, Bulleid was engaged in the production of his new 'Merchant Navy' Pacifics, and Bond had just been put in charge of the workshops at Crewe, so neither could be spared. Consequently, here being no other obvious candidates for the post, without further delay, Matthews appointed Edward Thompson as CME of the LNER, the decision being confirmed at the Board Meeting on 24th April, 1941, just 19 days after Gresley's passing.

Hughes added that Thompson was known to display a brusque manner on occasion, and in his latter years under Gresley the two were obviously at odds. Why this should be is not at all clear, as over the years Gresley gave Thompson successive promotions, but Vi Godfrey [Gresley's daughter] told [Hughes] that her father had said that Thompson had been 'disloyal', so clearly something serious must have developed between the two men.

Thompson's tenure as chief mechanical engineer of the London & North Eastern Railway began when he was fifty-nine, too old to make as much of a mark as his predecessor, Nigel Gresley, who had three decades to establish his reputation. Moreover, on coming to office in 1941 Thompson had all the problems and diversions of wartime to occupy his attention. Deteriorating standards of maintenance, coupled with the inability of running sheds to maintain Gresley's celebrated conjugated valve gear, meant that the latter's three-cylinder designs were doing poorly in terms of failure rates. Thompson's ambition, it seemed, was to rid his railway of the Gresley valve gear, and he made a start by rebuilding with conventional valve gear Gresley's Cock o' the North class and also his pioneer Pacific, Great Northern. However, this process was not carried far. Before his retirement in 1946, he introduced two standard types, the B1 4-6-0 mixed traffic locomotive and a somewhat similar 2-6-4T (L1). Both these were easily-maintained two-cylinder machines of handsome appearance and good performance, although the B1 type, of which more than 400 units were built, was initially a rough rider. This last feature was a result of slack manufacture and Thompson's ambition to build a two-cylinder locomotive with 'harnmerblow' characteristics similar to a three-cylinder machine, for which worthy cause he balanced the reciprocating parts only to the extent of thirty per cent. Thompson's evident disrespect for much of Gresley's work aroused great animosity in some quarters, and it was said that he bore a grudge against his predecessor. There might have been some truth in this; he had after all served under Raven on the North Eastern Railway and probably resented the latter being passed - over in favour of the Great Northern Railway's Gresley when a chief mechanical engineer for the new LNER was appointed. But those who knew him said he was a man of charm, refinement, and kindness, though without close friends and rather lonely after his wife (Raven's daughter) died.

Hughes' Sir Nigel Gresley (page 73) notes that Thompson was "quoted as having said at the time" [of the 8F locomotive boilers constructed at Doncaster] "that they cost 70 per cent more than the similar LNER standard boiler of diagram 100E". It is noteworthy that Thompson hardly deviated from Gresley's overall policy on boilers..

Letter from E. Thompson to: Railway Gazette, 16th Nov. 1945

The Chief Mechanical Engineer, London & North Eastern Railway, Doncaster, November 6.

To the Editor of The Railway Gazettee. Sir – I have read with very great interest the article in The Railway Gazette on the subject of Sir Cecil Paget's experimental locomotive. It is of particular interest to me because I was an Improver in the Derby Locomotive Sheds at the time and I remember not only the engine but the secrecy which was observed concerning it. I worked in the shed with a particularly competent fitter who subsequently attained a very high position as a foreman at Derby, and I remember very well on one occasion that he told me he had been out for a run with this engine and that its performance was "absolutely astonishing".

Unfortunately in those days I was not allowed to come into any sort of contact with the locomotive, but I am proud to say that in later life the designer became one of my closest personal friends. I shall always look on him as one of the greatest British raliwaymen we ever had.

Youn faithfully, E. Thompson

References to

P. Grafton, Edward Thompson of the L.N.E.R. (1971).

Hughes, Geoff. Talking to Thompson. Part 2.

Steam Wld, 1992, (62)

50-3.

Notes and observations made of an "interview"

made by Brian Reed in 1948 with Edward Thompson; the record of which is kept

at the NRM. T. Worsdell was forced to retire due to the excessive patent

royalties paid to him by the NER. Wilson Worsdell according to Thompson was

lazy and spent his time fishing and on his estate in Norway, but he was a

mechanical genius. Thompson recorded how the upopular Works Manager at

Darlington, Ramsay Kendall, was engineered out of his position by deliberate

bad workmanship on the R1 class when manufacture was transferred there from

Gateshead. The locomotive was unworkable even by Driver Blades and on stripping

down it was found that the coupling rod centre-to-centre lengths varied by

up to a quarter of an inch and Kendall was asked to leave. He was replaced

by Norman Lockyer formerly Works Manager, Gateshead. Thompson had a poor

regard for Raven's engineering skills ("scarcely knew the difference between

an engine and a tender"), but he got on well with him and married his daughter.

Gresley was at daggers drawn with Raven. Thompson suggested rebuilding the

NER Pacifics with two cylinders of 21 in diameter and with the smokebox tubeplate

pushed back, but Gresley was not interested. Thompson considered the

J39 a failure compared with the NER P2 and P3 0-6-0s: the J39s were too powerful

in relation to the size of the big end bearings. He noted that the difference

in the boiler mountings made it difficult to interchange boilers between

the D49 and J39 classes. The rebuilt S3 class eliminated six eccentrics on

the crank axles and moved away from poor NER cylinder design. The rebuilt

S3 (B16/2) were better than the K3 class. Thompson considered GCR frame and

boiler design to be excellent, but most had poor cylinder layouts, especially

the 4-cylinder types. New construction was concentrated at Doncaster (larger

types) and at Darlington (smaller and medium sized locomotives). Boiler making

(except for the wide firebox types) and iron casting were concentrated at

Gorton where the castings were excellent. Cowlairs eventually had an excellent

foundry, but Darlington lacked this ability as Lord Airedale, Chairman of

the Locomotive Committee insisted on using Kitson's who supplied the monobloc

and valve chest castings for the Z class Atlantics. The facilities at Stratford

were cramped but Thompson increased productivity there. Whilst Works Manager

at Doncaster he had prepared plans to concentrate all new construction there.

The LNER followed NBR practice in having a separate Running Department. The

GER had divorced running from A.J. Hill and given it to F.V. Russell, but

he was a difficult man and Col. W.J. Galloway, a GER director insisted that

it was transferred back to Hill. The author questions how the interview was

conducted: was it face-to-face or by letter?

Hardy, R.H.N. Memories of Thompson.

(Steam Wld, 1992 (59), 6)

Important in that Hardy and Thompson shared the same elite public

school and this enabled the young Hardy privileged access to the CME and

contains some of the relatively few personal characteristics about Thompson

recorded.

Specific designs

Hughes (Steam Days, (28), 18) discusses Thompson's 1000 locomotives, noting how the B1 class could be constructed from existing standard parts (the design was far more "standard" than the far "less standard" LMS class 5. Hughes also discusses the Pacifics constructed by rebuilding existing locomotives, attributes the K1 to Thompson rather than Peppercorn and notes the displacement of some of Thompson's new construction/rebuilding by purchases from the Ministry of Supply: Austerity 2-8-0s and 0-6-0STs.

B1 4-6-0

Hardy (Steam Wld, 1992 (59), 6) considered that the B1 could match the LMS class 5 "any day of the week" and "were lighter on coal and fast and free for steam. Futhermore, the injectors were infinitely better. Both classes were rough, but Hardy considered that the class 5 was more rugged.

Portraits

Bonavia, Michael R. The

birth of British Rail. p. 56

Group photograph at opening of Rugby Locomotive Testing Station on

19 October 1948 with O.V.S. Bulleid, Louis Armand, F.W. Hawksworth, Peppercorn,

Parmentier, Stanier and H.G. Ivatt

Papers

Railway power plant in Great Britain.

Proc. Instn mech. Engrs,

1947, 157, 235-9 + 4 plates. 12 illus., diagr. (s. &

f. els.), 2 tables. (Centenary Lectures).

The other speakers were Bulleid, H.G. lvatt and F.W. Hawksworth.

Policy respecting locomotive developments has been largely influenced by

the factors governing production in the immediate post-war period, and

investigation into advanced designs with a view to production of such units

has not formed any part of the L.N.E.R.’s policy. The company’s

resources of finance, manpower, and facilities, are being concentrated on

restoring the basic locomotive stock to its previous level of mechanical

reliability, and to the building up of a fleet of modem locomotives of improved

performance and greater availability to replace many of the now obsolete

classes.

The same broad principles of design, which have proved so successful in the

past, are being maintained in the eight new standard designs selected as

representative of the traction needs of the company. Two of these designs

are illustrated in Fig. 6, Plate 2, (Thompson A2/3) and Fig. 7, Plate

3.(L1)

Altogether some 150 of these engines are already in traffic, and larger orders

are now in hand both in the company’s workshops and in the workshops

of contractors.

It is not expected that within the limited territorial boundaries of the

LNER anything approaching the monthly mileages of 25,000, and the mileages

between overhaul of some 200,000 miles, so common in America to-day, can

hope to be realized. Nevertheless, the fact that steam-locomotive mileages

of the high order attained in America are possible, undoubtedly points to

considerable possibilities in our own case in the future. One of the essential

requirements, in order that a wider range of operation such as this may be

approached, is a controlled system of boiler-water treatment throughout the

whole line. Research into valve events points to future development in one

or two directions. If the piston valve is retained its diameter can with

advantage be increased.

On the other hand poppet valves seem a logical field for study provided that,

with the speeds visualized on the large poppet valves, adequate means are

provided to close the valves positively and rapidly after emission of steam.

From the point of view of simplification of motion details, especially to

the middle cylinder of three-cylinder designs, poppet valves have marked

advantages.

Much consideration has been given to the question of the steel firebox and

its many advantages are not overlooked—in particular the elimination

of objectionable overlap of plates at rivet joints which, by welding fireboxes

complete, are avoided. Galvanic action is removed by eliminating dissimilar

metals, and weight is lessened, enabling higher evaporation per unit of weight

to be obtained. Nevertheless, steel fireboxes require the best of waters

for their use, and water softening to the pitch required to achieve immunity

from scale has not yet been reached in this country.

Whilst the foregoing represents the general trend of development for steam

locomotives, it should not be assumed that the L.N.E.R. is without interest

in the advances which have been made in the practical application of alternative

forms of traction for main-line services. The gas-turbine, for example, is

meriting considerable thought but is as yet insufficiently developed to enable

future policy to be determined.

Diesel. In the field of traction employing internal-combustion power

the LNER has now formulated schedules for the introduction of a not

inconsiderable number of Diesel railcars over a wide range of secondary services.

The railcars proposed are of the Diesel-mechanical type, each car having

two power units, each of 105 b.h.p. The basic seating capacity is to be

forty-eight passengers, and the cars are to work either singly, in multiple

units with or without trailers, or, alternatively, two units with a standard

type coach in between them. The cars employ preselective electro-pneumatic

gear change, and maximum designed speeds in high and low ratio are 65 m.p.h.

and 46 m.p.h. respectively, thus giving a fast, secondary line, limited

passenger-service for which steam traction is neither economical nor sufficiently

adaptable.

The introduction of Diesel-electric units for shunting purposes has been

made: engines of this type are undergoing trial. The units are of 350 b.h.p.,

and six-coupled, with nosesuspended traction-motors on the two outside pairs

of coupled wheels. Double-reduction gearing is provided between the motors

and the driving wheels in order that the motors may have a reasonable speed

of rotation when the locomotive is operating at the very low speeds of

“hump” shunting work. A further shunting locomotive is expected

to be delivered for trial shortly; this engine, of 200 b.h.p., employs a

mechanical drive.

Electric. The Doncaster locomotive works has built the prototype 0-4-4-0

all-electric, mixed-traffic locomotive of 1,868 b.h.p., for the

Manchester-Sheffield electrification scheme.

Conclusion. The LNER has concentrated its design policy on the orthodox

steam locomotive rather than on other forms of traction, because of the greater

maintenance advantages which accrue from operating a large fleet of

straightforward, simple, and similar machines.

For adequate power, three-cylinder propulsion has been favoured in preference

to four, and often where the same power could have been produced by two

cylinders. Fundamentally, the more nearly the variable crank-effort of a

reciprocating engine can be made to approach uniformity, the greater will

be the advantage derived for traction from a given adhesive weight.

Peppercorn mentioned the advantages of three-cylinders, standardization,

and the prospects for diesel traction..

Circular letter to all Soutern Area enginemen: consumption of locomotive

coal. London: LNER Liverpool Street, January 1938.

3pp letter signed A.H. Peppercorn, Locomotive Running Superintendent,

Southern Area. Copy in Millennium Library, Norwich (Norfolk Local Collection).

Use of coal, water and steam in the locomotive. LNER, 48pp.

Reprinted from the LNER Magazine 1937. Diagrams show both good

and bad fires, and correct regulator settings. Ottley 10555. Copy in Millennium

Library, Norwich (Norfolk Local Collection).

Biography

Marshall and Journal Institution Locomotive Engineers, 1950, 40, 711-12: born Leominster (Herefordshire) on 29 January 1889 and died Doncaster 3 March 1951. Educated privately and at Hereford Cathedral School. Joined Great Norther Railway in 1895 as a Premium apprentice at Doncaster Locomotive Works under Ivatt and latterly Gresley. On completion of apprenticeship, he gained running shed experience, and subsequently was appointed an Assistant to the District Locomotive Superintendent at Ardsley, later occupying a similar post at Peterborough. During the 1914-18 war he served in the Chief Mechanical Engineer's Department of the Royal Engineers in France, and, after carrying out various duties was finally appointed Technical Assistant to the Chief Mechanical Engineer at the Directorate-General of Transportation, France.

On demobilisation he became District Locomotive Superintendent at Retford, and subsequently returned to Doncaster as Assistant-in-Charge of the wagon shops. In 1921 he was appointed Assistant to the Carriage & Wagon Superintendent at Doncaster and on the formation of the L.N.E.R. in 1923 became Carriage & Wagon Works Manager at Doncaster; and in 1927 was appointed to a similar post at York. His next appointment, in 1933, was that of Assistant Mechanical Engineer at Stratford, and in 1937 he became Locomotive Running Superintendent of the LNER Southern Area. In 1938 he was promoted to the post of Mechanical Engineer, North Eastern Area at Darlington. Mr. Peppercorn returned to Doncaster for the second time in 1941, when he was appointed to the dual post of Assistant Chief Mechanical Engineer of the LNER and Mechanical Engineer, Doncaster. Four years later he relinquished the latter post to give closer assistance to Edward Thompson then Chief Mechanical Engineer, and to take charge of the department in his temporary absence. Peppercorn was himself appointed Chief Mechanical Engineer in 1946 which position he held until his retirement at the end of 1949. Notable for his A1 and A2 Pacifics which abandoned the extraordinary cylinder layout adopted by his predecessor.

Rogers' Thompson & Peppercorn notes his shyness and abhorence of swearing. He had been a keen sportsman: rugby and cricket when young, and angling and golf in later life. His first wife died in 1935 after only seven years of marriage: in 1942 he met Pat who became his second wife in 1948.

Preface to George Dow's Steam horses

When Chief Mechanical Engineer, Eastern & North Eastern Regions of British Railways Pep contributed a preface to George Dow's Steam horses: "There is something about the alliance of man and steam horse-of human skill with huge mechanical strength-that never fails to capture the imagination of those who admire an intricate piece of machinery, brilliantly designed, skillfully put together, and beautifully handled.

It is this alliance of man and one of his most powerful and influential inventions-one of the few, moreover, that as Roger Lloyd has said 'has not been prostituted to purposes of lying, hatred, and slaughter' and still possesses 'a queer innocence and decency'-that is the main theme of this book. Mr Dow describes the sort of men who serve the locomotive, from her designers to those who feed, groom, and water her and under whose hands she often performs prodigious feats of speed, strength, and endurance. Any footplate man or loco. engineer will tell you that no steam horse ever behaves exactly like any other steam horse, whatever stable she comes from.

The details of day-to-day maintenance that turns a locomotive out on to the iron road at the highest pitch of efficiency are only less spectacular and not less fascinating than the stories of the famous record-breakers and how they won their laurels.There is very little in the life of a railway engine with which Mr Dow does not deal in this book; her component parts, the outstanding achievements of great designers. past and present, the building of a modern locomotive, and the evolution of both passenger and freight types from the pre-grouping days of many British railways till the day they became simply-British Railways .

How vividly he describes thrilling contests on British metals from the race to the North in the 'nineties with the lightly-loaded trains of those days to the tremendous load-hauling feats performed on the old London Midland & Scottish and London & North Eastern Railways in pre-war years, and the recapture for Britain of the world's steam locomotive speed record of 126 m.p.h by LNER class A4 Pacific Mallard on the 3rd July 1938. How illustrious in railway istory are the names re-called-names of the elite among steam horses, Hardwicke, City of Truro, Flying Scotsman, Lord Nelson, Royal Scot, and the striking streamlined Silver Link unlike anything which has been seen on, British lines before or since. Some of the anecdotes that Mr Dow relates will be known only to a very few intimate friends of the present-century designers.I venture to think that this book will be enjoyed no less by locomotive and other engineers than by youthful collectors of engine-numbers and the passenger who likes to stroll up the platform to see what breed of steam horse it is that stands snorting with apparent impatience to be off.

Bond's paper Years of transition is immensely important for establishing the high mileages attained by the A1 Pacifics. Harrison also wrote appreciatively about the Pappercorn Pacifics.

Last Chief Mechanical Engineer of the LNER in the eighteen months preceding nationalization in 1948, Peppercorn had little time to make his mark, although his two classes of Pacific, incorporating LNER tradition, were successful. He began as a premium apprentice with the Great Northern in 1905, served in the Royal Engineers in the First World War and spent much of his railway career in the running rather than the constructional side. In his final office, he moderated the tension and ill-will generated by his predecessor Thompson's drive against some of the negative aspects of the Gresley heritage.

See : Locomotive Carriage and Wagon Review, Aug. 1946.

Portraits

Bonavia, Michael R. The

birth of British Rail. p. 56

Group photograph at opening of Rugby Locomotive Testing Station on

19 October 1948 with O.V.S. Bulleid, Louis Armand, F.W. Hawksworth, Edward

Thompson, Parmentier, Stanier and H.G. Ivatt

| RETURN TO Home Page Top of this Page |

|

| Registered Charity No 290944 | Company Limited by Guarantee No 1862659 |